Shandong Zhanhua Yonghao

News

Add: GENGJU VILLAGE NORTH ONE KILOMETER,,ZHANHUA DISTRICT,BINZHOU CITY,SHANDONG PROVINCE,CHINA.

+86-543-7596322

How are people cured of HIV? Here's everything you need to know

Only a few people have been cured of HIV, but scientists are working to develop cures that could be accessible to more of those infected.

.png)

Timothy Ray Brown, known as the "Berlin patient," was the first person cured of HIV. (Image credit: T.J. Kirkpatrick/Getty Images)

In the past 20 years, a handful of people have been cured of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes AIDS, through intensive medical procedures.

Several more people have received the treatment and also appear to be HIV-free, but it's too soon to definitively declare these patients cured. For now, they're described as being in long-term remission, and their cases are considered "possible" cures. All these patients received stem cell transplants, with cells collected either from adult bone marrow or from umbilical cord blood.

Scientists reported the first definitive HIV cure in 2008, and since then, two more definitive cures and two possible cures have been reported. The most recent reports of such cases — one definitive cure(opens in new tab) and one possible cure(opens in new tab) — came out in early 2023.

Experts say these treatments may become more common in upcoming years as scientists better understand them. However, for now, these treatments are risky and largely inaccessible to the tens of millions of people living with HIV worldwide. Thankfully, drugs for HIV, called antiretroviral therapies (ART), can greatly extend HIV-positive people's lifespans and cut their risk of spreading the virus, but the medications must be taken daily and for life, can interact with other drugs(opens in new tab) and carry a small risk of serious side effects(opens in new tab).

So scientists hope these exceptional cure cases will pave the way to new, more-accessible treatment strategies that will rid more people of the virus.

Here's what we know about curing HIV.

What treatments can cure HIV?

All of the people cured and potentially cured of HIV have been treated with stem cell transplants. In addition to being HIV-positive, all the patients had some form of cancer, specifically acute myeloid leukemia or Hodgkin's lymphoma. These cancers affect white blood cells, a key component of the immune system, and can be treated with stem cell transplants.

To simultaneously treat these patients' cancers and HIV, their doctors sought out stem cells from people with two copies of a rare genetic mutation: CCR5 delta 32. This mutation disables a protein on the cell surface called CCR5, which many HIV strains use to break into cells. The virus does this by first latching onto a different cell surface protein and changing shape; then, it grabs hold of CCR5 to invade the cell. Without CCR5, it's essentially locked out.

(Some less-common HIV strains use a different surface protein, called CXCR4, instead of CCR5, and some strains can use both, according to a 2021 review in the journal Frontiers in Immunology(opens in new tab). Therefore, prior to their transplants, patients were screened to ensure that most or all of the virus in their body used CCR5.)

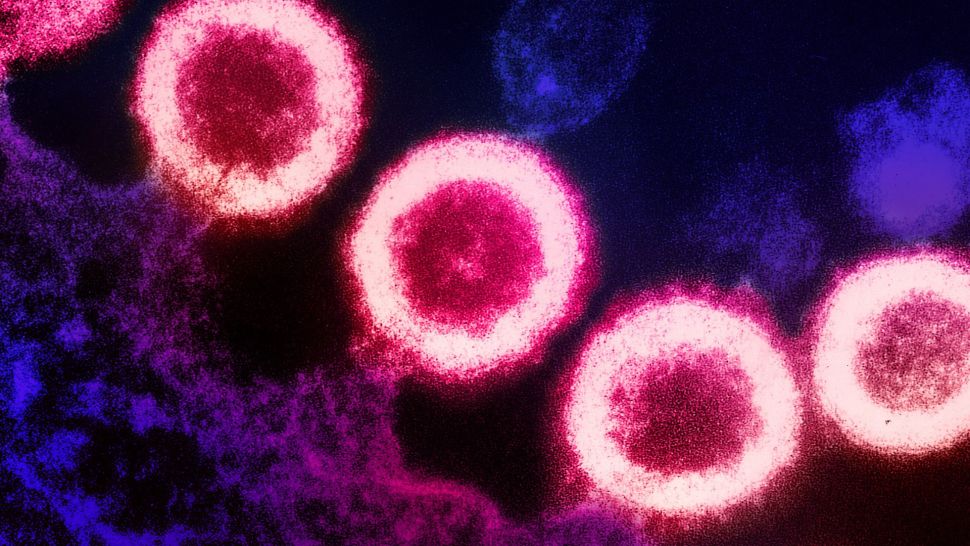

HIV (pink) infects cells of the immune system (purple), as pictured here. (Image credit: NIAID via Flickr)

To prepare for the transplant, the patients underwent aggressive radiation or chemotherapy to wipe out the cancerous and HIV-vulnerable T cells — a type of immune cell — in their bodies. This weakened patients' immune systems until the transplanted stem cells could produce new, HIV-resistant immune cells. For some time post-transplant, patients also took immune-suppressing drugs to avoid graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), where the donor-derived immune cells attack the body.

Most patients received stem cells taken from the bone marrow of adult donors. These cells must be carefully "matched," meaning both the donor and recipient must carry specific proteins, called HLAs, in their body tissues. An HLA mismatch can result in a catastrophic immune reaction.

One patient — the first woman to undergo a stem cell transplant for HIV and enter long-term remission — received stem cells from umbilical cord blood that had been donated at the time of a baby's delivery. These immature cells adapt more easily to a recipient's body, so the patient had to be only "partially matched." She also received stem cells from an adult relative, to help bolster her immune system as the umbilical cells took over.

Because umbilical cord stem cells don't need to be a perfect match and they're easier to source than bone marrow, such transplants could potentially be offered to more patients in the future.

.jpg)

However, HIV-positive patients shouldn't undergo the risky procedure unless they have another disease that requires a stem cell transplant, Dr. Yvonne Bryson(opens in new tab), director of the Los Angeles-Brazil AIDS Consortium at the University of California, Los Angeles and one of the cured patient's doctors, said at a March 2023 news conference.

How many people have been cured of HIV?

As of March 2023, three people have been cured of HIV and two more are in long-term remission.

In addition to Timothy Ray Brown, the cured individuals include the London patient, later revealed to be Adam Castillejo; and the anonymous Düsseldorf patient. The two possible HIV cures include a man known as the City of Hope patient and the New York patient, the first woman to receive the treatment.

At present, there's no official distinction between being cured and being in long-term remission from HIV, Dr. Deborah Persaud(opens in new tab), who helped oversee the New York case and is the interim director of pediatric infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins, said at a March 2023 news conference.

"[The Düsseldorf patient] was likely the second person to be cured, but the team was really conservative, and stopped antiretroviral therapy after several years, and waited a long time to conclude that he was cured," Dr. Steven Deeks(opens in new tab), an HIV expert and professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the patient's case, told Live Science in an email.

The Düsseldorf patient was treated in 2013, continued ART for nearly six years and has now been off the medication for more than four. Meanwhile, Castillejo received his transplant in 2016, stopped ART a little over a year later and was confirmed cured in 2020, before the Düsseldorf patient.